Accelerating patient access to cell and gene therapies

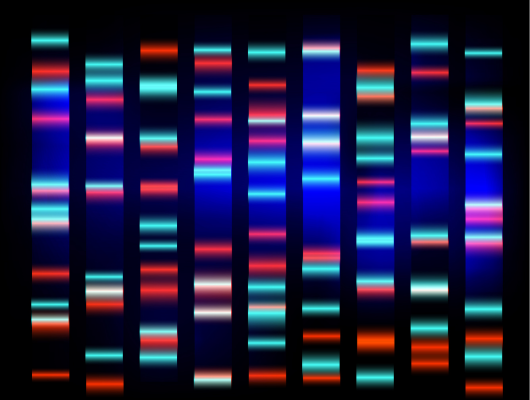

As the first human genome was being deciphered two decades ago (an astronomical effort that took 13 years and about $3 billion), it was hard to predict that sequencing techniques would go on to become affordable, scalable and accessible enough to convince the healthcare buyer. Today, genetic sequencing is leading the way in integrating genomic technologies into public health system routine care, more specifically for screening (identification of individuals who may be at risk of a condition) and diagnosing (confirmation that the individual is affected by a condition). The success of genomics can be attributed to the fundamental technique of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and the multitude of enabling technologies that were developed to underpin it. As a result, new genomic technologies, such as cell and gene therapies, are now emerging with the potential to transform healthcare – should they become available to the many patients in urgent need of new treatment options.

What are the present challenges and necessary solutions that are needed to accelerate patient access to cell and gene therapies?